©️ Margery Thomas

Many herbaceous ie non-woody plants on the reserve are wind-pollinated, including the grasses that define the heathland areas, and the sheeps sorrel (Rumex acetosella, another dioecious plant) whose tiny female flowers, reduced to the essentials for fertilisation, cast a rusty haze over short grass. The heather (Calluna vulgaris) on the heaths is pollinated by insects and wind. A plant mainly of high rainfall areas, the anthers containing the pollen are protected from rain by closed petals, but wind can shake pollen out when insects aren’t flying. Studies have also shown that thrips that live in the tiny heather flowers move to other flowers thus transferring pollen.

As the showier flowers start to open in order to produce the next generation, different techniques, attract the pollinator insects, bees, butterflies and moths. Energy goes into scent, colour on petals/sepals and markings to guide into the centre of flower where nectar may be produced, so that pollen, usually heavier and stickier than tree pollen, may be caught on fur or hairy legs, and taken to another plant. In the main bog, the insectivorous sundew Drosera rotundifolia has a challenge, needing insects to pollinate the small flowers that open one at a time, while needing insects to land on the leaves a few centimetres below to be consumed for nutrients.

Some plants have developed a back-up to pollination by external forces, self-pollination, or cleistogamy, from the Greek kleistos for closed. On the reserve, in early autumn, two violets, Viola paulustris and reichenbachiana, both axiophytes or indicators of habitats of conservation importance, produce colourless flowers close to the rootstock almost underground, which produce some pollen which immediately fertilises the same hidden flower, resulting in the usual capsule of seeds at soil level which bursts virtually underneath the main plant. Likewise in the main bog, bog asphodel Narthecium ossifragum, another axiophyte, is known to resort to cleistogamy in very adverse conditions.

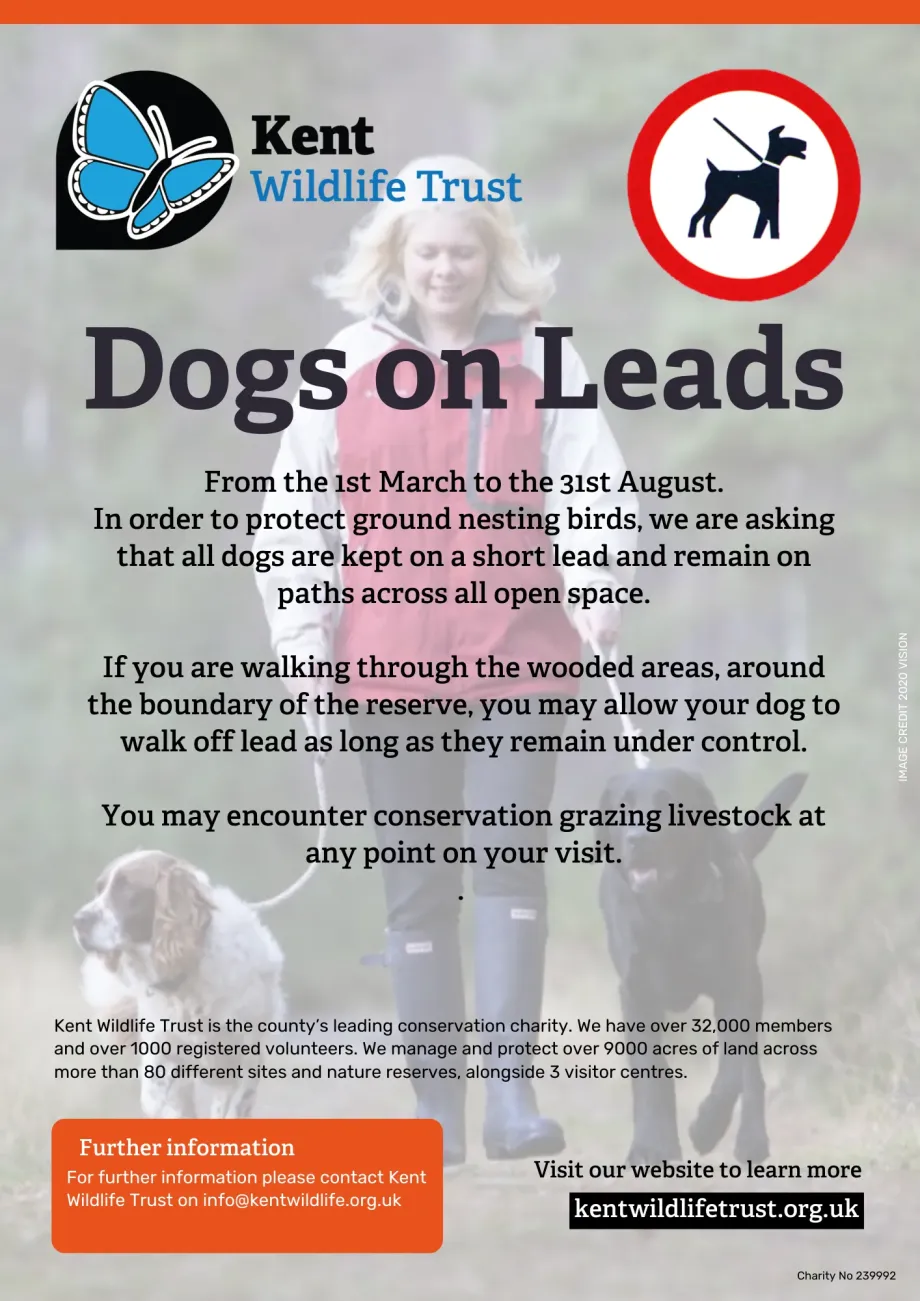

Meanwhile the birds (and bees) are preparing to produce their next generations with nest-building and courtship. Please help us protect the nests at or close to ground level on the open heathland which are extremely vulnerable to disturbance.

As the weather begins to warm and day length increases many of our bird species will start to think about nesting. On Hothfield low and ground nesting species like linnets, stone chats and yellow hammers are particularly sensitive to any disturbance. We are therefore asking for people to consider these species and walk on the paths and keep dogs on short leads whilst out in the open areas of the reserve. Together we can share these spaces with nature and encourage more rare species onto our amazing reserve like resident Dartford warblers and nightjars. The woodland periphery walk will still be a dogs under control zone but please bear in mind that livestock are also present on reserve. We will be asking for this until the end of the nesting season in September.