Podcast transcript

Rob Smith: It's pretty simple, really. Insects and all the other bugs do literally millions of essential jobs. Of course, they pollinate plants, and without pollination there would be no fruits and seeds, and so in very short order, no food. But of course, they also eat lots of the stuff that we don't like to think about. All the dead skin that falls from our bodies, the food that we and all other animals excrete, the gigantic quantities of leaves and twigs that fall from plants. You name it, they eat it. And without their tireless, hungry efforts, we would soon disappear under a mountainous blanket of detritus. So bugs really do matter.

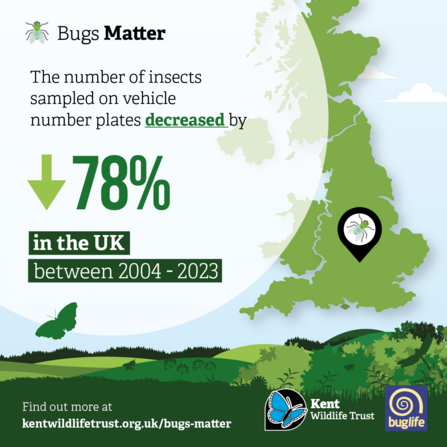

And that's why it's so alarming to think that their total numbers have fallen dramatically in recent decades - by at least 60% in the UK, according to the organisation Bug Life. And no one is really very certain exactly why, other than it probably has something to do with us and the way that we live and farm in the modern world. So what can we do about it? Practically, what can you do to help?

Well, one thing you could do is to join in the Bugs Matter Survey. It's a really straightforward citizen science project that anyone who drives a vehicle can join in by counting the number of bug splats on your number plates. Seriously. I met up with Doctor Lawrence Ball, who is the Lead Ecological Data Analyst at Kent Wildlife Trust, to find out more.

Dr Lawrence Ball: So what we're hoping is that a lot of people across the country get involved in this excellent citizen science project called Bugs Matter, which involves us kindly requesting that the nation counts the number of insects on their number plates. And this can hopefully tell us about how insect abundance is changing over time.

Rob: And broadly speaking, the figures that have been gathered in previous years are pretty alarming, aren't they?

Lawrence: Yeah, absolutely. So we're comparing our data which has started in 2021 and has run in subsequent years with a reference year that was undertaken by the RSPB in 2004. So we're looking almost sort of a 20-year period. And, and compared to 2023, yeah, we're seeing about 78% decline in the number of insects splattered on number plates. So it's a, it's a big figure. It's really concerning.

Rob: I mean that is a huge drop off, isn't it? You know, 80% less very nearly is, is almost off the charts. So, what's that being put down to? Is it, is it just the cars? Have we caught so many insects with the cars, is that what's going on?

Lawrence: So there's a wide range of drivers of insect decline and they're fairly common ones that we all know for other biodiversity as well. So the big ones are land use change, you know, the huge change in the types of land cover that we've got now compared to a thousand years ago or three hundred years ago. Pollution obviously is quite a key one for insects that have their life cycles within aquatic water bodies. So nitrates running off farmland, herbicides, pesticides, they can all affect insects quite severely.

Climate change as well, combined with habitat fragmentation. So with a warming climate, insects and other species need to move to sort of north up to northern latitudes or to higher altitudes. So here in Kent, we don't have a huge range of altitudes. So we need our insects and invertebrates to be able to move north. And we just have too much farmland and fragmented natural habitats for that to happen, you know.

Rob: OK so it's not directly the cars that the issue. It's everything else. It's the general background hum of environmental damage.

Lawrence: It is. Yeah. Yeah. There's not been a great deal of studies on the number of insects that have been killed by cars. I think there was one study in the US that found a few million insects along one road in a year or something like that. It was quite a large figure. But you've got to think when you compare that to all the known drivers of insect decline and other biodiversity decline, they're gonna be stronger factors.

Rob: So you're after people joining in with the Bugs Matter survey. What do you actually have to do to do that? Is it tricky?

Lawrence: No, it's straightforward. I can show you if you want.

Rob: OK go on then. So, pulling out of your pocket, you've got the Bugs Matter app on your phone, so that's easy to find. Is it – you just search Bugs Matter in your kind of play store?

Lawrence: Absolutely. Yeah. On Apple and Android. So you downloaded the app and you open it up and it'll ask you to create an account, which is really straightforward. It just requires your name and postcode and then you just accept the sort of privacy policy and that sort of thing. Once you've signed up, you then tap ‘Start a journey’, and I've already got my vehicles added. So you can see I can select vehicles here, my vehicle and my wife's vehicle. But if this was the first time I signed up, it would ask me to add a vehicle. So just like this and you pop in your registration plate number and that uses a clever API to get quite a lot of details about your car. Now, this sounds a bit scary, but it's actually really important. So when we do the analysis, we want to know how different shapes and sizes and colours and types and widths and heights of vehicles will affect the rates at which bugs are splattered.

Rob: So, what, can the colour can make a difference?

Lawrence: We don't, well, I include it in the analysis – whether, it doesn't usually have a sort of strong influence on the on the data, you know, within the data.

Rob: But a car that's kind of aerodynamic, I guess a lot more insects will go over the top of. A car that's like, you know, square feet, if you got a Hummer – a tank, one of those kind of things – that's gonna have a different number of insects that splatter on the front of it, just the air flows different.

Lawrence: Yeah, absolutely. So we've seen each year we've run the survey HGV's splat statistically significantly more bugs than other types of vehicles. And that must be because of that, that huge front, front end. Yeah.

Rob: And so you get the app, you start a journey, it follows your map. And then how does the app know how many insects have splattered on your car?

Lawrence: Great. So when you've completed your journey and you've reached your destination, should we go down to the number plate here?

Rob: Yeah, you literally, you count how many insects are splattered on the number plate?

Lawrence: Count the number here, and you then take a photograph and submit the photo and the bug count along with whether it's rained or not. That's quite important. We need to know if it's rained, they might have been washed off and therefore, it's not accurate data and yeah, and as simple as that.

Rob: So it's not reliant on your counting, it's the photo that matters. Is it sort of like some clever AI jiggery pokery that actually counts the insect splats?

Lawrence: That's a really interesting question. So it's something we've been looking into and we did do a pilot study to see if we could AI count bug splats. We have parked that for the moment just due to limited resources, but we would hope to go back to that. So at the moment it relies on the count of the user and, and yeah, we, we trust everyone can count insects accurately.

Rob: So, so you have to just make sure you clean off the clean off your number plate before the start of the journey so that you've got a clean slate literally to start with. And so I mean, there is a degree of trust then to make sure that people are doing this properly. How, as a scientific experiment, I guess if you're asking thousands, tens of thousands of people to join in, there's a kind of a margin of error that you have to take into account. But in general terms, people are pretty good?

Lawrence: Yeah, yeah. I mean, yeah, we, the only possible thing is that people might not submit zero journeys not realising that they're important. But of course they are. If you drive hundred miles and don't splat any bugs, that's a really important bit of data. But yeah, we have full faith in the quality of the data that's coming in. We have a lot of data. So five/six/seven thousand journeys each year covering sort of over a hundred and twenty thousand miles of journeys all across the UK Scotland, Northern Ireland, right down to Cornwall and all over.

Rob: And there are differences in the number of bug splats that you see across the country?

Lawrence: Yeah. So we've tended to see more insect splats in the North, so in Scotland and the North of England, than we do down in the South and South East.

Rob: OK interesting.

Lawrence: Which could be due to the larger areas of agriculture and farmland down here.

Rob: How many do we get in Kent?

Lawrence: Yeah. So in Kent we have a lot of journeys recorded, which is fantastic and a lot of our members and a lot of other people in Kent here are getting involved, which is really great. So thank you to those people. And in terms of the actual stats of decline, we are seeing quite a steep decrease in Kent. So the number of insect splats in Kent alone declined by around 88 to 89% between 2004 and 2023. And it's one of the steepest declines of any county.

Tipula maxima © Frank Porch

Rob: That's really scary. And as a sort of broad thought, why does it matter? You know, why should people get involved in this study?

Lawrence: What's really nice about Bugs Matter is it's really obvious how the data you're collecting is useful. You know, you, you count the number of insects on your number plate. And if you do it for a few years and throughout the survey season, you might even notice yourself some different trends happening. You know, if you do drive lots of country lanes, you might splat more bugs than if you do a motorway journey. And I think it's, it's that sort of obvious link between the data you're collecting and how it's useful, that's really quite unique with Bugs Matter. And of course, it's super easy. It's a couple of minutes before you get in your car, couple of minutes at the end. And obviously we don't, we want to limit the amount of journeys we're making, but we all have to, a lot of us have to drive places. So you could, if you do this, it just makes it, you know, that little bit more worth making that journey, I think.

Lawrence: From a personal perspective, why is it important to you how many insects we have flying around?

Rob: Yeah. So I'm passionate about the environment and conservation, and I'm kind of lucky to have been from a very young age. So I used to volunteer with the RSPB and other wildlife trusts when I was sort of 14 and have carried on working in conservation now until my mid 30s. So it's, yeah, it's it means a great deal to me that we have invertebrates because they underpin ecosystems. They underpin nature, you know, without them, we lose a lot of ecosystem services that we need, of course, pollination, decomposition, and all those key things that we benefit from. But you know, there's so many insects, there's so many other animals (including insects) that feed on insects and invertebrates that they're just so key to, to the whole ecosystem structure. I would hate to think what would happen without invertebrates or with a, a very small number of them.

Rob: The whole thing would fall apart.

Lawrence: I think it would, yeah, it would be quite an unpleasant situation, yeah.

Rob: So the Bugs Matter project, when's it running until? Or is it just ongoing forever?

Lawrence: It's ongoing forever, yeah. The longer we collect data and the more data we collect each year, the more useful it is. And we'd really love sort of more involvement from companies and businesses and organisations that have either fleets of vehicles, lots of drivers that are making lots of journeys everyday. And that would really boost the amount of data we have. And yeah, of course we want this to carry on as long as we need to then start to understand if the data can really tell us about the background rates of insect decline. If we only run it for a few years, it could be weird weather, weird stochastic factors in those years affecting what we're seeing.

Rob: Oh that’s a good word, ‘stochastic’. What does that mean?

Lawrence: Unexpected, unknown environmental reasons perhaps... summer 2022 for example, when we got 40 degrees, is the number of bug splats that we counted that year a good indication of the background number of insects? Possibly not as as it would be in a typical year. So if we can collect data over say 5/10 years, 15 years, even longer, we start to really have more faith than it's reflecting actual insect abundance and change.

Rob: So – download the app, splat some bugs, get some good, good data.

Lawrence: Yeah, absolutely. Yeah, if as many people can take part as possible, that's just what we want.

Rob: Doctor Lawrence Ball there, Kent Wildlife Trust’s Lead Ecological Data Analyst and a jolly nice chap he is too. So if you want to join the Bugs Matter survey, just search online for Bugs Matter and that will bring up the Bug Life website. You can find out all the details there. A warning though, you will find yourself spending much longer than you meant to looking at all the amazing stuff on the Bug Life website. There's a brilliant Bugs directory which will help you identify insects and spiders and jellyfish and all the invertebrates are on there. And then you'll be reading up on the mating habits of the gold fringed masonry, or the favorite food of the five banded Weevil wasp, or where you're most likely to find a wart biter bush cricket. And before you know it, it's two o'clock in the morning and getting up for work is going to be a real problem. Anyway. It's well worth taking a look at the Bug Life website. This has been a Wild Rover Media production. I'm Rob Smith, and until next time, do go wild in the country.